The idea of designing mobile games is a funny one. In theory, there isn't anything about making games for smartphones or tablets that's fundamentally different from any other form of game design. The formal properties of games as systems are the same across any genre or platform, and so the design process tends to look relatively similar, whether you're trying to make the next Farmville, Call of Duty, or chess.

In practice, though, creating a successful mobile game can be a very different beast. So many different concerns — from market saturation and lack of discoverability, to usage patterns and form factor issues — can make it feel like making a good mobile game is like turning on "hard mode" as a designer.

All of these various factors at play mean that most successful mobile games tend toward elegant rulesets. That is, they strive to be capable of deep, meaningful play, but that meaning needs to arise from a minimal set of simple rules. There's certainly a place for more ornate and baroque games, but very few successful mobile games tend to hew to that style, no matter what your metric for success is.

So how do we achieve these sorts of elegant designs we want in our games? Let's look at two defining characteristics of mobile games — play session length and methods of interaction — and see a few ways we might approach thinking about designing systems that suit the platform.

Play Session Length

People play mobile games differently than most other kinds of games. Players demand games that are playable in short bursts, such as while they're waiting in line or on the toilet, but they also want the ability to partake in more meaningful, longer-term play sessions. Most studies peg the average iOS game session length at somewhere between one and two minutes, but at the same time, most mobile games are in actuality played at home rather than on the go. Striking a balance to make your game fun and rewarding in both situations is a really challenging problem.

To help us think about designing for both of these contexts, it's useful to think about a game as a collection of feedback loops. At any given moment of a game, you have a mental model of the game's system. Based on that, you're going to perform some action that will result in the game giving you feedback, which will in turn inform your mental model.

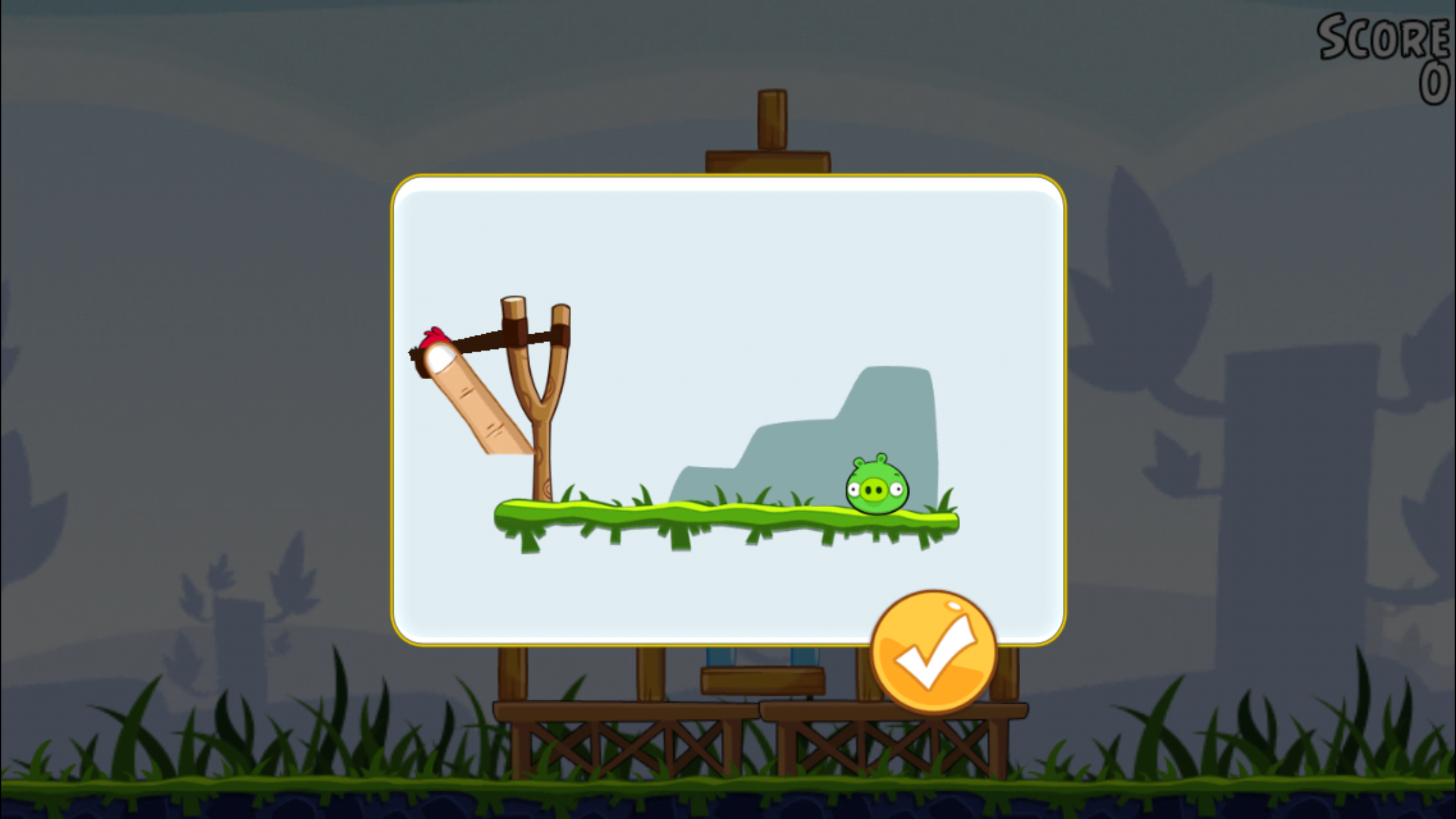

The key thing about these feedback loops is that they're fractal in nature; at any given moment, there could be any number of nested feedback loops at play. As an example, let's think about what is happening when you play a game of Angry Birds.

Let's start at the level of each individual move you make. Flinging an individual bird across the map gives you the satisfaction of accomplishing something, but it also gives you feedback: did you destroy the blocks or pigs you thought you would? Did the arc your bird took (still visible onscreen after the bird has landed) mirror what you thought it would? This information informs your future shots.

Taking a step back, the next most atomic unit of measurement is the level. Each level also acts as its own closed system of feedback and rewards: clearing it gives you anywhere from one to three stars, encouraging you to develop the skills necessary to truly 'beat' it.

In aggregate, all of the levels themselves form a feedback loop and narrative arc, giving you a clear sense of progression over time, in addition to providing you with a sense of your skill, relative to the overall system.

We could keep going with examples, but I think the concept is clear. Again, this isn't a game design concept that is unique to mobile games; if either the moment-to-moment experience of playing your game or the overarching sense of personal progression is lacking, your game likely has room for improvement, no matter the platform.

This becomes particularly relevant when thinking about the problem of play session length, though. It's possible to have a game with fun moment-to-moment gameplay, while still having the smallest systemic loops be sufficiently long that trying to pick it up for a minute or two while in line wouldn't be fun. That same minute or two in Angry Birds lets you experience multiple full iterations of some of the game's feedback loops, giving a sense of fun even in such a short playtime. The existence of higher-level feedback loops means that these atomic micro-moments of fun don't come at the expense of ruining the potential for longer-term meaningful play.

The Controller Conundrum

Most platforms for digital games — game consoles, PCs, and even arcade cabinets — have a larger number of inputs than smartphones or tablets. Many great mobile games find unique ways to use multitouch or the iPhone's accelerometer, rather than throwing lots of virtual buttons on the screen, but that still leaves iOS devices with far less discrete inputs than most other forms of digital games. The result is a difficult design challenge: how can we make interesting, meaningful, and deep game systems when our input is constrained? This is a relatively frequent topic of discussion for game design students — creating a one-button game is a classic educational exercise for aspiring designers — but the restrictions of iOS frequently make it more than an academic concern. Ultimately, it's a similar problem to that of gameplay session length: how do you create something that's simple and immediately approachable without giving up the depth and meaningful play that other forms of games exhibit?

One useful way for framing interactions in a game is to reduce the formal elements of the game down to 'nouns' and 'verbs.' Let's take the original Super Mario Bros. as an example. Mario has two main verbs: he can run and he can jump. The challenge in Mario comes from the way the game introduces and arranges nouns to shape these verbs over the course of the game, giving you different obstacles that require you to apply and combine these two verbs in interesting and unique ways.

Of course, Mario would be much more boring if you could only run or jump. But even the six buttons required to play Mario (a four-directional d-pad and discrete 'run' and 'jump' buttons) are in many ways too complex an input for an ideal touchscreen game; there's a reason there are few successful traditional 2D platformers on iOS.

So how can we add depth and complexity to a game while minimizing the types of input? Within this framework of nouns and verbs, there are essentially three ways we can add complexity to a game. We can add a new input, we can add a new verb that uses an existing input, or we can take an existing verb and add more nouns that color that verb with new meaning. The first option is generally going to add complexity in the way we don't want, but the other two can be very effective when done right. Let's look at some examples of mobile games that use each of these ways to layer in additional depth without muddying the core game interactions.

Hundreds

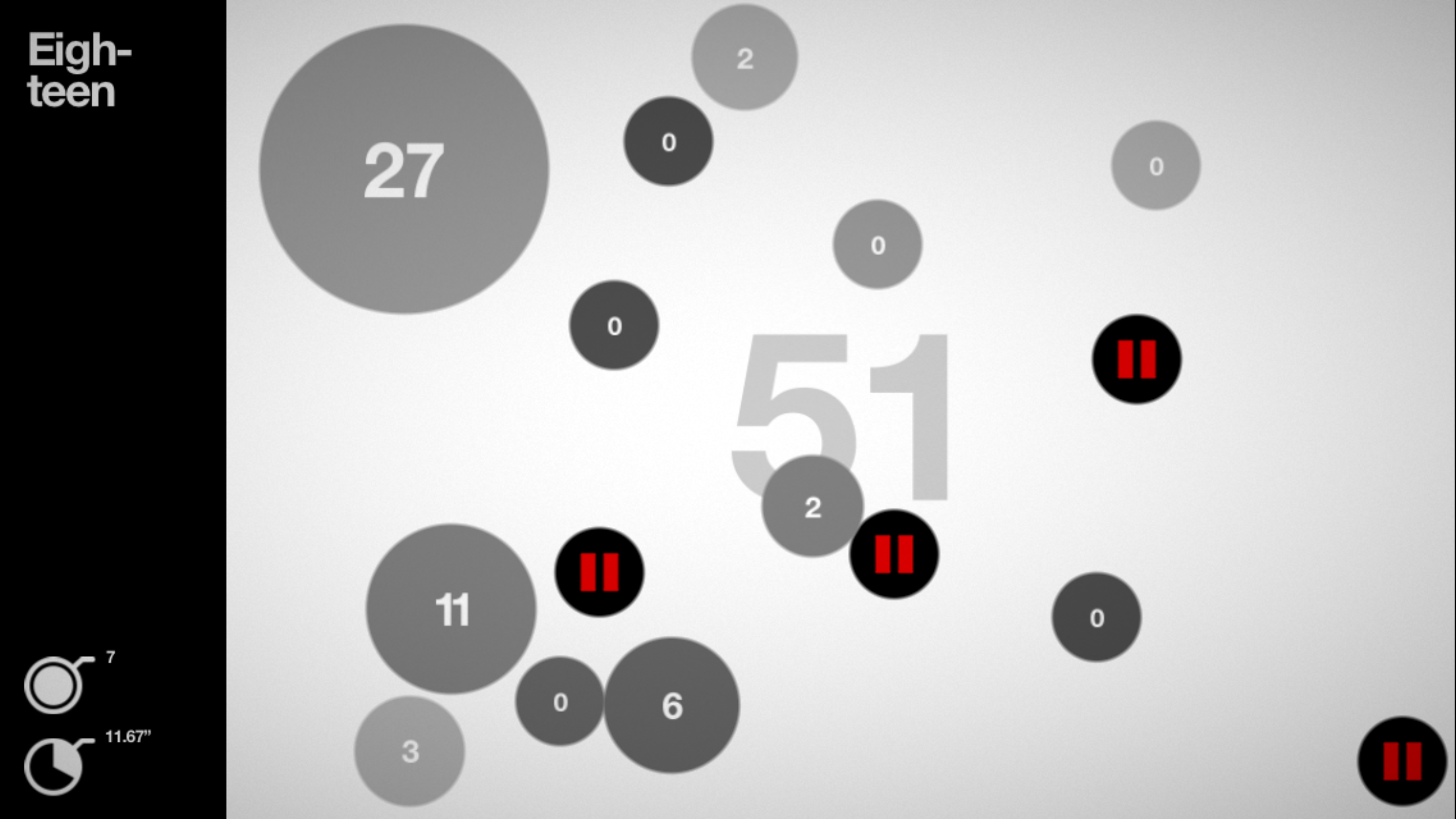

The game Hundreds 1 is a great example of adding in new verbs without complicating the way you perform the game's verbs.

Initially, the only verb at your disposal is "touch a bubble to grow it." As the game progresses, new types of objects are introduced: bubbles that slowly deflate over time, spiky gears that puncture anything they touch, ice balls that freeze bubbles in place. It would be easy for this to become overwhelming to the player, but crucially, nothing ever breaks the input model of "tap an object to do something to it." Even though the number of possible verbs balloons to a pretty large number, they cohere in a way that keeps it simple. The interaction between these elements is rich — moments such as using the ice balls to freeze the dangerous gears, rendering them harmless, are particularly satisfying — but the fundamental way you interact with the system stays simple.

Threes

The puzzle game Threes 2 exemplifies the other approach, managing to layer in complexity and strategy without making any changes to the things you can do in the game.

Throughout the game, its rules remain completely constant. From beginning to end, the only verb in your tool belt is "swipe to shift blocks over," with no variation at all. Because of the way the rules of the system create new objects at a predictable rate, complexity emerges naturally as a result of progression. When the screen only has a few low-numbered blocks at the beginning of the game, decisions are easy. When you're balancing building up lower-level numbers with managing a cluster of higher numbers, that same one verb suddenly has a lot more meaning and nuance behind it.

Both of these are great examples of games that manage to offer simplicity on the surface but great depth underneath by carefully managing where and how they add complexity and meaning to their verbs. The approach between the two might be different, but both do a laudable job of shifting some of that complexity away from the lowest levels of the game to make them more accessible.

Elegance

We've now explored two different lenses we can use to think about designing games. Thinking about your systems in terms of nested feedback loops, and managing the relative lengths of one iteration of each loop, can help you design something that is fun for both 10 seconds and an hour at a time. Being cognizant of the way you add complexity to your game through the way you handle your game's verbs can help you increase your game's strategic depth without sacrificing accessibility to new players.

Ultimately, these two concepts explore similar ground: the idea that gameplay depth and systemic complexity, while related, are not necessarily equivalent. Being conscious about at what layer of your game the complexity lies can help make your games as accessible as possible to new players, and encourage short pick-up-and-play game sessions without sacrificing depth or long-term engagement.

Again, neither of these concepts is particularly new to the world of game design. In particular, design blogger Dan Cook talks a lot about nested feedback loops in his article, "The Chemistry of Game Design," and Anna Anthropy and Naomi Clark's book, "A Game Design Vocabulary," has an insightful exploration of what it means to conceptualize your game in terms of verbs.

But these problems are exacerbated on mobile. The mobile context makes it vital to keep your lowest-level loops and arcs as short and self-contained as possible, without losing sight of the bigger picture. The practicalities of touchscreen controls make adding complexity and nuance at the input level difficult, making it that much more important that your more higher-level systems can still provide rewarding advanced play for experienced players. The unforgiving nature of mobile games means that elegance in design isn't merely ideal, but a necessity; recognizing that simple doesn't have to equal shallow is vital to designing good mobile games.

-

The basic concept of Hundreds is simple: each level has a bunch of bubbles bouncing around, each with a number inside it. The larger the number, the bigger the bubble. While you are touching a bubble with your finger, it turns red, grows larger, and its number increases. When you stop touching it, it stops growing and turns black again, but it maintains its new number and size. Once the sum of all on-screen bubbles is at least 100, you've beaten the level. However, if a circle touches another circle while it is red (i.e. being touched), you need to restart. ↩

-

If you don't know Threes, you might instead be familiar with the more popular clone, 2048. Threes presents you with a 4x4 game grid with a few numbered squares, where every square's number is either a 1, a 2, or a 3, doubled some number of times (3, 6, 12, 24, etc.). When you swipe in any direction, every square that is capable of doing so will shift over one space in that direction, with a new square being pushed onto the game board in an empty square from the appropriate side. If two squares of the same number are pushed into each other, they will become one square whose number is the sum of them together (1s and 2s are different; you must combine a 1 and a 2 to get a 3). When you can no longer move, your score is calculated based on the numbers visible on the board, with higher numbers being worth disproportionately more than lower ones. ↩